Robert Greene delves into human envy in his description of the Law of Covetousness. Envy, he explains, is an emotion that’s difficult for many people to admit they feel, primarily because it’s associated with pettiness and meanness. However, envy is a part of human nature. Greene suggests that by understanding and admitting our envious feelings, we can transform this potentially destructive emotion into a powerful tool for self-improvement and understanding others.

The Law of Covetousness addresses the human inclination to desire what others possess. This can be material items, status, relationships, talents. Often rooted in envy or insecurity, this desire can lead individuals to make irrational decisions, harbor resentment, or even sabotage themselves and others.

Envy can also lead to achievement. Rather than allowing envy to lead us into destructive behaviors or self-loathing, we should see it as a mirror reflecting our deepest desires and what we value. When we recognize our envy, we can analyze it and use it as a guide to improve ourselves.

Three examples.

Antonio Salieri (1750-1825) and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791). Salieri, a contemporary of Mozart, was a court composer with a decent reputation. However, upon recognizing the sheer genius of Mozart, Salieri reportedly felt deep envy. In popular culture, like the play and movie Amadeus (1984), Salieri’s envy drives him to destructive behavior, illustrating the negative potential of unchecked envy.

The movie suggests that Salieri poisoned Mozart. However, Erin Blakemore writes (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/A-German-Composer-uncovered-collaboration-between-mozart-and-salieri-180958154/)

In 1824, attendees of a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony were handed anonymous leaflets that described Salieri forcing Mozart to drink from a poisoned cup, and the rumor was so deliciously suggestive that it inspired a dramatic dialogue from Pushkin, which was later turned into an opera. “Amadeus”, which was adapted from a stage play by Peter Shaffer, carried the rumor into the present day. All this despite the fact that historians can’t really find any evidence for any ongoing personal hatred between the men.

E. Blakemore (in Smithsonian Magazine, 16 Feb 2016)

Blakemore also reported that in 2016, a German composer and musicologist searching for compositions of Salieri’s students uncovered a collaborative work between the two musicians, “Per la Ricuperata Salute di Ofelia” (“For the recovered health of Ophelia”).

Surely there was envy — from Mozart as well, who had expressed his displeasure at the strong Italian influence at the court, meaning Salieri — such feelings may also have pushed both musicians to higher achievements in their craft and, in at least one case, a collaborative project.

Coca-Cola and Pepsi. The corporate world provides ample examples of covetousness. The rivalry between Coca-Cola and Pepsi is as classic as their taste. The desire to outdo a close rival (or envy of their success) can drive innovation and marketing strategies. It can also lead to very bad decisions. Such is the case with the “Pepsi Number Fever” fiasco in the Philippines.

In February 1992, Pepsi Philippines introduced a promotion where numbers printed inside the caps of their beverage bottles, including Pepsi, 7-Up, Mountain Dew, and Mirinda, could win prizes. Prizes varied from 100 pesos to a grand prize of 1 million pesos, about US$40,000 at the time. The promotion boosted Pepsi’s sales and market share considerably to 26%. Winning numbers were broadcasted on TV nightly, and by May, 51,000 prizes, including 17 grand prizes, were claimed. Due to its success, the campaign was extended five weeks beyond its original end date.

In May 1992, the networks announced number 349 as the grand prize number. PepsiCo had produced only two bottles with that winning number, each with a unique security code. However, due to an oversight before extending the contest, 800,000 bottle caps were printed with number 349 without the security code, theoretically worth US$32 billion. Thousands flocked to claim their winnings. After an emergency meeting, PepsiCo offered 500 pesos ($18) to each holder of the incorrectly printed caps as goodwill, ultimately costing them US$8.9 million.

Many holders of the 349 bottle caps rejected Pepsi’s compensation offer and formed the 349 Alliance. This group boycotted Pepsi products, held protests, and rallied outside Pepsi and governmental offices. Although most protests were peaceful, violence ensued when a homemade bomb aimed at a Pepsi truck killed a schoolteacher and a child in Manila in February 1993. By May, three Pepsi employees in Davao died from a grenade attack in a warehouse. PCPPI faced further hostility with death threats, and nearly 37 company trucks faced damage or destruction. Some 689 civil suits and 5,200 criminal complaints for fraud and deception were eventually filed against Pepsi. In 2006 the Philippine Supreme court laid the issues to rest when it ruled that “PCPPI [Pepsi] is not liable to pay the amounts printed on the crowns to their holders. Nor is PCPPI liable for damages.”

In the immediate aftermath of the scandal, sales of Pepsi products in the Philippines plunged from 26% to 17% of the total market share but recovered to 21% by 1994, which remained steady to this day (Coca Cola has 75%).

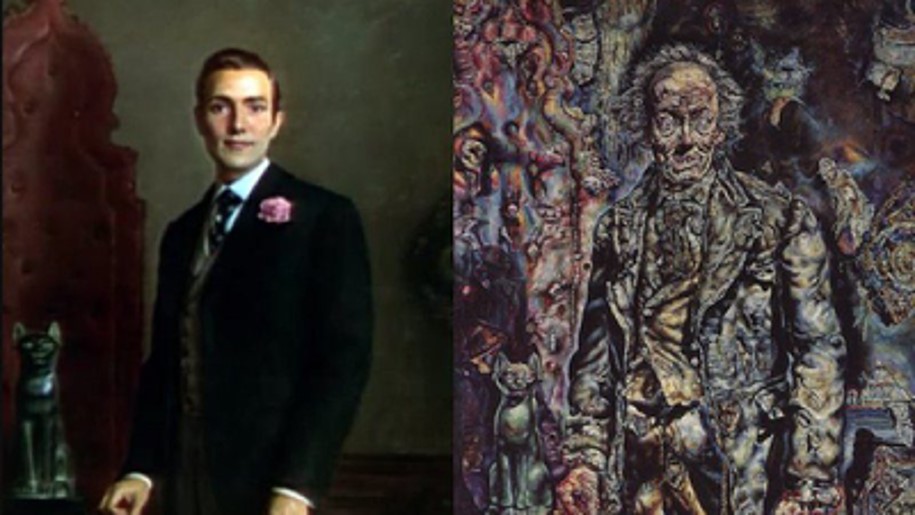

Oscar Wilde’s novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) offers a vivid exploration of the dangers and seductions of envy as a vice waiting to consume the soul. In the novel, Dorian Gray is introduced as a figure of innocence, a blank slate, whose beauty attracts admiration from all quarters. However, it’s this very beauty that becomes the root of his envy.

Under the influence of Lord Henry, Dorian becomes acutely aware of the transient nature of youth and beauty. Faced with a portrait that captures his youthful perfection, Dorian is not filled with pride or gratitude, but with a searing envy for the unchanging visage on the canvas. His desire to remain as unspoiled as the image in the portrait, while letting it bear the scars of his sins, symbolizes the destructive nature of envy. Dorian’s wish is granted, but at a severe cost. As he indulges in every vice and sin, free from the repercussions on his appearance, the portrait becomes more and more grotesque, mirroring the corruption of his soul.

Wilde uses Dorian’s tale to warn against the peril of envying what one has, of desiring permanence in an impermanent world. Envy, rather than leading to satisfaction, results in an insatiable hunger for more, pushing the envious further from contentment. Dorian’s downfall is not just due to his hedonistic pursuits, but stems from his envy of a painted image, an unattainable ideal.

In the end, envy proves to be Dorian’s undoing. Unable to bear the sight of his true self, as reflected in the portrait, he destroys it, inadvertently ending his own life.

Wilde’s narrative serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of envy, illustrating that it not only corrupts the soul but can also lead to one’s downfall. In seeking what we do not have or cannot be, we risk losing ourselves.

Instead of denying or repressing envious feelings, Greene suggests turning it into a powerful tool for self-awareness and growth.

Here are some ways to manage the Law of Covetousness:

Be self-aware. Recognize and admit when you’re experiencing covetous feelings. Understanding when and why you feel this way is the first step in managing these emotions.

Find contentment. Instead of constantly looking at what others have, cultivate gratitude for what you already possess. Keep a gratitude journal that focuses on your blessings. Be grateful for the not-so-good things as well.

Evaluate desires. Ask yourself if your desires are genuinely yours or if they’re shaped by external influences like societal norms, peer pressure, or fleeting trends.

Limit exposure. If you notice that certain platforms (e.g., social media) intensify your feelings of covetousness, reduce your time on these, take breaks.

Seek self-improvement. Instead of envying others, channel that energy into bettering yourself. Focus on personal growth, acquiring new skills, or pursuing genuine interests.

Shift perspective. Understand that everyone has their own struggles and challenges, even if they’re not visible. What might seem perfect from the outside often isn’t.

Practice generosity. Celebrae others’ achievements and be happy for their successes. This can also foster positive connections.

Reframe comparisons: If comparison is inevitable, compare yourself to your past self rather than others. Celebrate growth and progress.

Seek memories, not things. Focus on finding genuine happiness and fulfillment in your life’s purpose, activities, and relationships, reducing the need to covet what others have.

Set personal goals. Instead of desiring what others have, set your own goals based on what truly matters to you. Celebrate when you achieve them, irrespective of others’ paths.

The Law of Covetousness can work for you if you focus its energies on genuine personal growth and happiness. When you feel grounded in your journey and values, the allure of what others possess diminishes.

(Q.C. 230812)

Rumi defines envy as the “non-acceptance of the good in others. If we accept that good, it becomes inspiration”. 😉😚

LikeLike