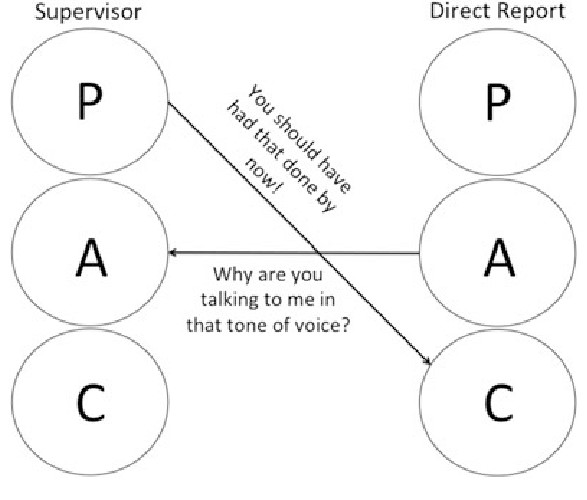

I learned yesterday about transference. This happens when you are triggered by someone’s behavior or words to act like a Child (emotional) or a Parent (authoritative) toward that person, recapitulating a similar exchange with a parent/authority figure or child that occurred in your past.

Transference is common; it is not always negative. For example, when a peer of mine talks about games, I tend to go into Child mode and deal with this person like another Child — we then get creative, finding joy in bouncing around new ideas. Negative transference can happen. Search for “triggered” or “karen” on Youtube to see what I mean.

Usually transference is not disruptive, even the negative ones. However, I know some colleagues who are so easily triggered that I avoid interacting with them outside of work.

So, how do we know transference is taking place? Let’s take a look at boss/subordinate relationships and start with transference behaviors exhibited by subordinates.

1. One is overly sensitive and selective with regard to what he pays attention to in the behavior of others.

2. One uncritically favors certain interpretations over possible others.

3. One’s responses to others can be traced to beliefs held about oneself, others, and the world.

4. One tends to behave in such a manner as to invite responses which are consistent with and confirm his expectations. Manipulation.

Here are examples of transference exhibited by one who is a boss.

1. He offers advice rather than listen to the subordinate’s experience. He does not leave much room for the subordinate to reflect and decide on her next action.

2. The boss inappropriately discloses personal experiences, stories about himself.

3. The boss doesn’t have boundaries with the subordinate.

4. The boss makes judgments related to his perspective, not the subordinate’s.

5. The boss pushes the subordinate to take action that she is not ready for.

6. The boss is too worried about the patient, as if he wants to save her.

7. Boss asks for irrelevant details and is overinvested in the subordinate’s story.

8. The boss wants to relate to or socialize with the subordinate outside of the professional setting.

9. The boss gets angry with subordinate over a belief they don’t agree with.

These same behaviors also manifest in transference between peers.

How can we deal with transference in the office?

Here are some strategies to address transference at work. These strategies apply whether you or another is experiencing the transference.

Be self-aware. Strive to recognize when you are experiencing transference reactions. This involves acknowledging and understanding your emotional responses to colleagues, which may be influenced by past experiences.

Maintain professional boundaries. Distinguish between personal emotions and professional conduct. Avoid allowing unresolved personal issues to affect work relationships or decisions.

Communicate openly, sincerely, and honestly. If you find yourself reacting strongly to a colleague or superior, consider discussing your concerns or feelings with them in a professional and non-confrontational manner.

Seek feedback. Encourage open dialogue and feedback from colleagues and supervisors. Their perspectives can provide valuable insights into any misunderstandings or miscommunications that may be fueled by transference.

Resolve conflicts. If transference leads to interpersonal conflicts, address them promptly and professionally. Engage colleagues who are experienced in resolving these.

Develop yourself professionally. Invest in personal and professional growth to enhance your emotional intelligence, communication skills, and conflict resolution abilities.

Seek therapy or counseling. If transference significantly affects your well-being or job performance, consider seeking professional help outside of the workplace. A trained therapist can help you explore the origins of your feelings and develop strategies for managing them.

Seek a mentor or coach. Find one from among experienced colleagues or supervisors. They can provide guidance, perspective, and support in navigating complex workplace dynamics.

Involve HR. If transference issues involve misconduct, harassment, or other violations of workplace policies, consider involving your organization’s Human Resources department. HR can provide mediation and guidance on resolving such issues.

Get some training in conflict resolution. Some organizations offer conflict resolution training programs to help employees develop skills for handling difficult workplace situations, including those related to transference.

Transference can also be made to work for us as a positive force. It can be challenging. Transference often involves powerful emotions and subconscious patterns, so turning it into a constructive force requires self-awareness and deliberate efforts. Here are some strategies to make transference work for you:

Begin by examining your own transference reactions. Understand your emotional triggers and patterns. Ask yourself why certain individuals or situations trigger strong emotional responses.

Identify a positive trigger. Sometimes, people may transfer positive feelings onto others based on past experiences. For example, if you have positive feelings or admiration for someone due to transference, channel those emotions into motivation for self-improvement. Use this admiration as a source of inspiration.

If you have a mentor or colleague you admire, you are probably being triggered in a positive way to seek guidance AND to follow it. Explain your admiration and desire to learn from them. They may be more willing to support your professional growth.

Still, transference is based on memories, not here-and-now data. Ensure that your expectations of others are realistic and not based solely on past experiences. Understand that people are individuals with their own strengths, weaknesses, and motivations. Embrace the diversity of people, their beliefs and their feelings. Recognize that everyone is unique, and that transference may not always be a reliable guide to understanding others.

Making transference work for you involves emotional intelligence, and a willingness to not play manipulative games.

Transference in the workplace is a common occurrence. Recognizing and addressing it in a constructive and professional manner is a skill worth mastering.

(Q.C., 231230)